INVENTED ASSYRIAN IDENTITY

Religious Origins of Nations?: The Christian communities of the Middle East

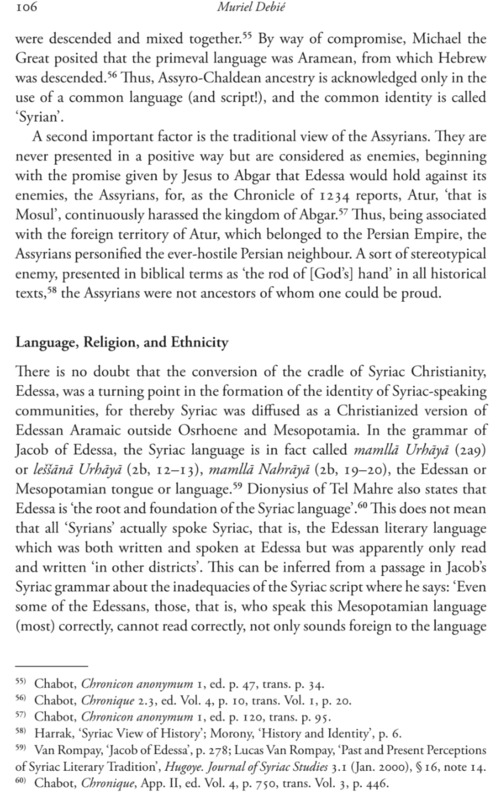

The author highest the fact that a connection to an Assyrian-Chaldean ancestry, as witnesses in the Chronicle of Saint Michael the Great, is only acknowledged in the use of a common language, i.e Aramaic and not an ethnic one. The author also confirms the fact that the tradition view of the Assyrians was presented in a negative and were not an ancestor the early Arameans would be proud of.

Oeuvre d'Orient

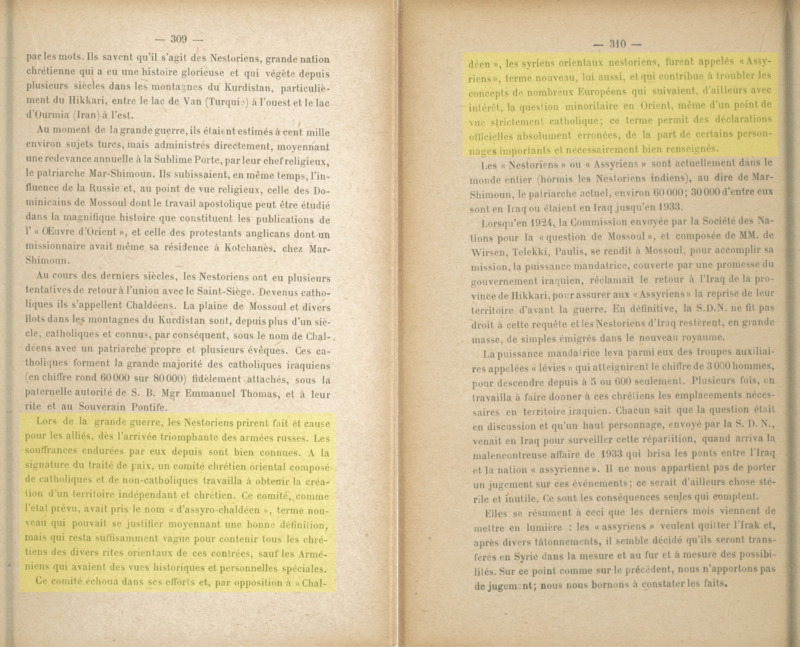

"During the Great War, the Nestorians sided with the Allies from the triumphant arrival of the Russian armies. The sufferings they endured from then on are well known. At the signing of the peace treaty, an Eastern Christian committee, composed of Catholics and non-Catholics, worked to obtain the creation of an independent Christian territory. This committee, like the proposed state, adopted the name “Assyro-Chaldean,” a new term that could be justified with a good definition, but which remained sufficiently vague to include all the Christians of the various Eastern rites in those regions, except the Armenians, who had particular historical and personal aims. The committee failed in its efforts, and in opposition to “Chaldean,” the Eastern Syrian Nestorians were called “Assyrians,” also a new term, which helped to confuse the concepts of many Europeans who were following, with interest, the minority question in the East, even from a strictly Catholic point of view; this term allowed absolutely erroneous official statements by certain important and necessarily well-informed figures."

The author describes the Nestorians, an Eastern Christian population long based in the Hakkari mountains between Lake Van and Lake Urmia. They lived under Ottoman rule but dealt directly through their patriarch Mar Shimun and were influenced by Russia as well as by Dominican and Anglican missions. Over the centuries some communities reunited with Rome and became Chaldeans, a Catholic church with its own patriarch and bishops; the author says most Iraqi Catholics belonged to this group and estimates roughly sixty to eighty thousand at the time.

During and after the First World War a mixed Eastern Christian committee tried to obtain an independent Christian territory. For this project it adopted the new umbrella label “Assyro-Chaldean,” which the author calls vague enough to cover many Eastern Christian groups in the region except the Armenians, and the effort failed. In the same period the Eastern Syrian Nestorians began to be called “Assyrians,” another new label. The author argues that these terms led Western observers, diplomats, and even churchmen to confuse identities and make erroneous official claims. He adds that there were about sixty thousand Nestorians worldwide then (not counting the Indian Nestorians), around thirty thousand of whom were in Iraq until 1933. A League of Nations mission in 1924 examined their case but promised solutions did not materialize, and after the 1933 crisis with Iraq many among them wished to leave for Syria. The overall message is that the recent political and ecclesiastical names “Assyro-Chaldean” and “Assyrian” blurred distinctions among Eastern Christians and generated misunderstanding in European and official discourse.

Assyrian Ethnicity in Chicago

“Assyrians today may be Kurds, Turks, etc., with little possibility that these people have some of the ancient Assyrian blood-lines.”

“The Assyrians of today are not related to the ancient Assyrians at all—racially, ethnically, nor historically.” (cited by May Abraham from Dr. Kretkoff)

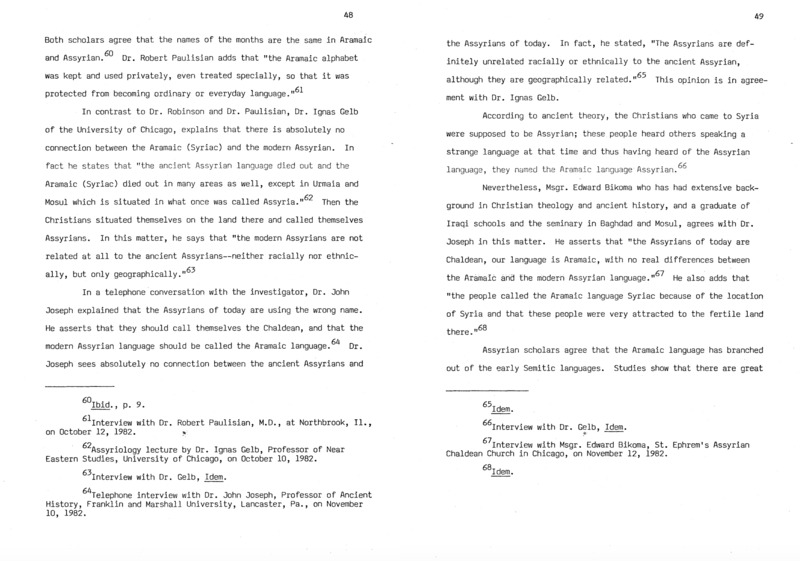

According to May Abraham’s pages (drawing on Ignace Gelb and John Joseph), the ancient Assyrian language had died out while the communities in question spoke Aramaic/Syriac; Joseph argues that today’s “Assyrians” are using the wrong name, should call themselves Chaldeans, and that what is called modern Assyrian should be called Aramaic. In this framing, “Assyrian” in the U.S. context functioned as an umbrella category that grouped Chaldeans, Jacobites, and members of the Church of the East from Iraq, Syria, Iran, Turkey, Kuwait, and Lebanon, who also used multiple everyday languages. Abraham underscores the point with two explicit claims from the text: “Assyrians today may be Kurds, Turks, etc., with little possibility that these people have some of the ancient Assyrian blood-lines,” and “The Assyrians of today are not related to the ancient Assyrians at all—racially, ethnically, nor historically” (cited by May Abraham from Dr. Kretkoff). Taken together, these statements present “Assyrian” as a modern, label-driven umbrella rather than a biologically or historically continuous identity from antiquity.

The Legacy of Mesopotamia

Stephanie Dalley writes that Syriac Christians from northern Iraq sometimes give their sons names like Sennacherib or Sargon and consciously identify with the ancient Assyrians, calling themselves “Assyrians” (Athoraye) rather than “Syriacs” (Suraye). She says this identification was fostered by Anglican missionaries working with the Nestorian Church in the nineteenth century and was later encouraged by the British in the late 1940s.

The Nestorian Churches: A Concise History of Nestorian Christianity in Asia From the Persian Schism to the Modern Assyrians

Aubrey R. Vine writes that British contact with the East Syriac Nestorians quickened after C. J. Rich’s encounters near Nineveh in the 1820s. Rev. Joseph Wolff carried a Syriac New Testament to England, and the British and Foreign Bible Society printed and distributed it around Urmi in 1827, while European governments protested after Kurdish attacks in 1830. The American Presbyterians opened a long mission at Urmi, while the Church of England worked through the SPCK, sending Ainsworth and later George Percy Badger, who earned goodwill by offering aid without trying to change doctrine and who sheltered the patriarch during the 1842 massacres. After the Nestorians appealed to Archbishop Tait in 1868, E. L. Cutts’s inquiry led to the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Mission to the Assyrian Christians in 1881, staffed by Rudolph Wahl, later Canon Maclean, Athelstan Riley, W. H. Browne, and finally Canon W. A. Wigram. The mission lasted until the Great War and moved its headquarters from Urmi to Van in 1903.

Vine explains that late 19th century Anglicans deliberately adopted “Assyrian” as the title for their mission among the East Syriac Nestorians. The Archbishop of Canterbury’s Mission used it in reports, school charters, and correspondence, and the term soon spread into wider English usage, so that newspapers, missionary journals, and general readers spoke of Assyrian Christians rather than Nestorians. The choice was both strategic and pastoral: it emphasized the community’s rootedness in the old Assyrian heartland, and it avoided the polemical associations of “Nestorian,” a term long tied to heresy and theological controversy. The new name also gave the community a dignified ethnonym that Western audiences could respect, while allowing Anglicans to support and reform the church without reopening ancient doctrinal debates.

Vine further notes that the community did not historically call itself Assyrian. In earlier Greek, Latin, and Western sources it was very often referred to as the Persian Church, because its catholicoi resided at Seleucia-Ctesiphon in the Sasanian Persian Empire, and its jurisdictions extended deep into Persia and beyond. Its own traditional title was the Church of the East, using the East Syriac rite and language. In Vine’s account, therefore, “Assyrian” was a modern, mission-driven designation, introduced and popularized by Anglicans, which gained legitimacy through long usage and was later embraced by many within the community itself, culminating in the modern name Assyrian Church of the East.

A Religious Encyclopedia

Philip Schaff (ed.) in A Religious Encyclopædia (1891), article “Semitic Languages,” states that “the Babylonian-Assyrian disappeared from history in the sixth century B.C., and their language survived only a few centuries,” whereas “the Syriac-Arameans lost their independence in the eighth century B.C., but continued to exist, and their dialect revived in the second century A.D. as a Christian language; and the Jewish Aramaic continued for some centuries (up to the eleventh century A.D.) to be the spoken and literary tongue of the Palestinian and Babylonian Jews.” In other words, as Schaff’s encyclopedia writes, the Assyrian-Babylonian tradition faded early as a historical nationality and language, while the Arameans lived on through enduring Christian and Jewish Aramaic traditions.

Fatal Ambivalence: Missionaries in Ottoman Kurdistan, 1839-43

Jessica R. Eber notes that the communities often linked with the “Church of the East” have been described by outsiders with several names over time, among them Syrian (referring to the liturgical language), Assyrian, Assyro-Chaldean, Old East Syrian Church, and Apostolic Assyrian Church of the East. She explains that Protestant missionaries popularized the label “Nestorian” to distinguish these Christians from the Chaldeans who entered communion with Rome in the fifteenth century. Eber also cautions against equating these communities directly with the Assyrians of the Old Testament, calling that linkage an inaccurate assumption that nevertheless influenced some nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholarship. Today, she observes, the term “Nestorian” is sensitive and often avoided, since many Christians use it pejoratively to denote schism or heresy.

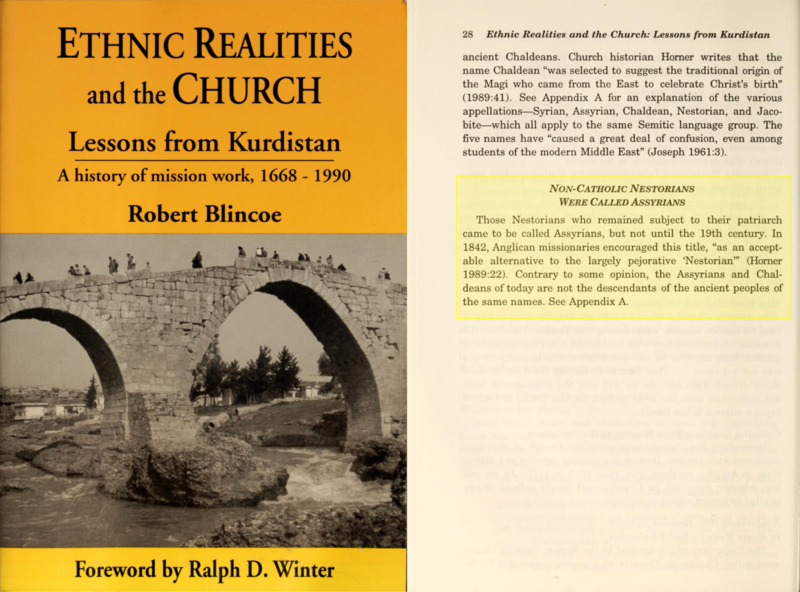

Ethnic Realities and the Church: Lessons from Kurdistan : a Historical Study of Missionary Work, 1668-1990

Blincoe writes that in the 19th century Anglican missionaries promoted the name “Assyrian” for members of the Church of the East who did not join the Roman Catholic communion. They saw it as a less pejorative alternative to “Nestorian.” Earlier labels such as “Chaldean” for those in communion with Rome and “Nestorian” for those who were not referred mainly to church affiliation and geography, not to ancient ethnic descent. Blincoe concludes that modern Assyrians and Chaldeans should not be regarded as direct descendants of the ancient Assyrians or Chaldeans.

The Development of Harvard University Since the Inauguration of President Eliot 1869–1929

David G. Lyon, Hancock Professor of Hebrew and Other Oriental Languages at Harvard, states that among the ancient Semitic peoples of Western Asia (Arabs, Arameans, Assyrians, Babylonians, Hebrews/Jews, Phoenicians; and in Africa, Ethiopians), the Babylonians and the Assyrians had “vanished long since.” He contrasts this with the modern scholarly recovery of their languages and literary treasures. Notably, Arameans are listed but not said to have vanished, underscoring a distinction Lyon draws between groups that disappeared as historical nations and those that did not.

The Concise Encyclopedia of Archaeology

Leonard Cottrell’s edited volume The Concise Encyclopedia of Archaeology, a collaborative work by 48 contributing scholars specializing in history and languages, explains that Assyrian power ended catastrophically with the sack of Nineveh in 612 BC. From that point, the Assyrians “disappeared as a nation for ever.” The entry adds that their modern image is mediated largely through Old Testament narratives and, more recently, through the decipherment of their own inscriptions, while emphasizing that no Assyrian nation survived beyond the seventh century BC.

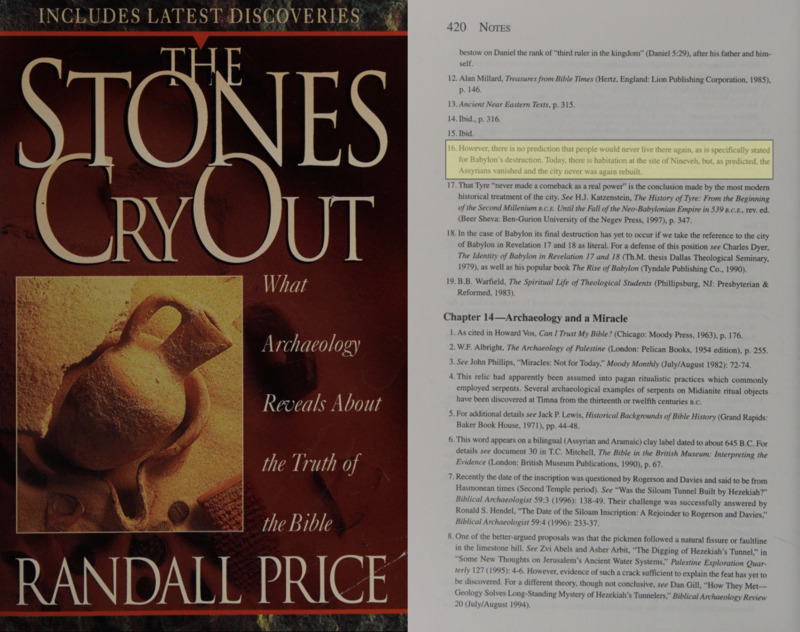

The Stones Cry Out

Randall Price contrasts biblical prophecies about Babylon’s permanent desolation with Nineveh’s fate. He notes that Scripture does not predict that no one would ever live at Nineveh again; in fact, the site is inhabited today, but not by Assyrians. What was foretold, he stresses, is that the Assyrians themselves would vanish and that the city would never be rebuilt as a functioning capital. Price therefore distinguishes between later settlement on the mounds and the absence of a restored Assyrian people or a revived Nineveh.