Items

In item set

Destruction of Assyria

Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt - Part XI (موسوعة مصر القديمة - الجزء الحادي عشر)

The disappearance of the Assyrians will always remain a unique and astonishing phenomenon in ancient history. Indeed, other kingdoms and empires similar to Assyria have disappeared, but their peoples have continued to live and be known after them. Recent discoveries have shown that communities ravaged by hunger and poverty have immortalized their ancient Assyrian names in various places, as we find represented in the city of “Ashur” for generations, but the main truth remained the same, namely that a nation that lived for two thousand

and extended its rule over a vast area, lost its independence. There are two reasons for this phenomenon: First, the Assyrians were immersed in sensual customs that could only lead to the suicide of their lineage, and the last two centuries of their history can be explained by a noticeable decline in their men, but this is not entirely due to internal wars. Second, we know that the Medes had brought a large number of Assyrian craftsmen who worked in metals and stones to their country, and we find many great works of art that were found in the cities of

Persepolis and Ekitana were made by craftsmen who learned their craft from groups from Nineveh. The Assyrian slaves taught their masters the art of seal carving.

In fact, no other country in the world was completely destroyed and plundered like Assyria, and no other nation, except for the Children of Israel, can give us a clear picture of the fate of these people.

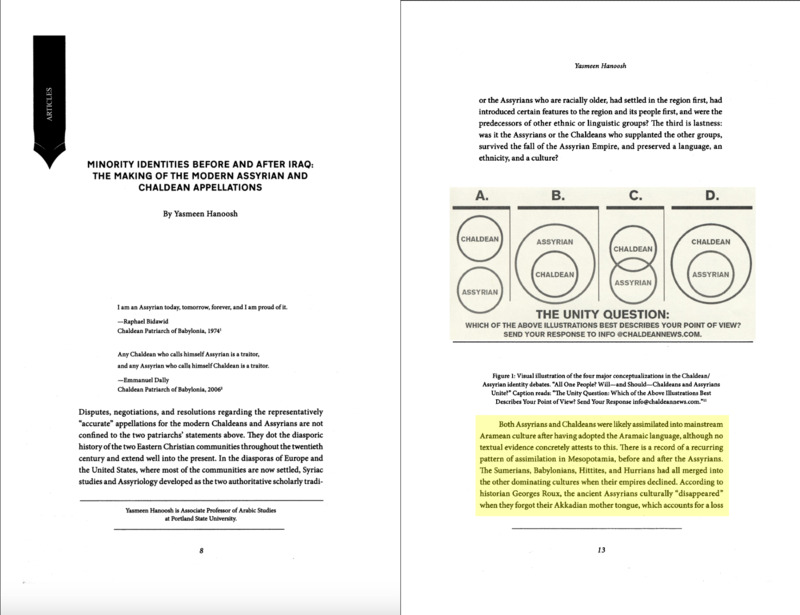

Minority Identities Before and After Iraq

Yasmeen Hanoosh writes that the Chaldean–Assyrian identity dispute is not about whether people survived the fall of Nineveh. Some indigenous population clearly continued, and Aramaic persisted. What changes is how later communities tell a monumental history that links themselves to antiquity. In that long view, she argues, both Assyrians and Chaldeans were likely absorbed into mainstream Aramean culture after adopting the Aramaic language, much as other Mesopotamian empires had been absorbed when their own languages and polities declined.

Yasmeen Hanoosh writes that when missionaries and early excavators from the United States and Britain arrived in Mesopotamia in the early nineteenth century, they met East-Syriac Christians who variously identified as Jacobites, Nestorians, and Chaldeans and who also used the umbrella label “Syrian Christians.” This encounter helped set today’s name disputes in motion: the title “Assyrian” as a living communal label had not yet fully revived and only later came to supplant “Nestorian,” while “Chaldean” marked those who had accepted union with Rome.

She emphasizes that Western church patronage and great-power politics shaped communal lines as much as theology. Missionaries became conduits to foreign protection: some communities sought the Church of England’s backing, others aligned with the Roman Church and the French consulate. Conversions in this period were often strategic moves for security rather than changes of belief.

By the mid-nineteenth century these ties produced concrete administrative outcomes. In 1844 the French consul secured millet status for the Catholic Chaldeans; the following year, aided by Protestant missions, the Nestorians also obtained millet recognition. Their patriarch, Mar Shimun, now held both spiritual leadership and an Ottoman salaried office. In Hanoosh’s reading, the Anglo-American missionary presence, together with Catholic diplomacy, fixed the modern split between “Chaldean” and “Assyrian” and helped popularize the latter as the standard non-Catholic name.

Finally, Hanoosh traces the Church of the East from its Persian base to Baghdad, then its later dispersal and recurring succession crises. Papal diplomacy created a Chaldean patriarchate, while the remaining Nestorians later embraced the revived name Assyrian. Her conclusion is that today’s identities grew from hybrid inheritances shaped by language shift into Aramaic, assimilation to Aramean culture, and modern missionary and imperial naming, rather than from a single unbroken national line.

Hurrians and Sabarians

Ignace J. Gelb writes that linguistic change has been a principal driver in how ancient peoples vanish from the historical record: the Sumerians, he notes, "lost their ethnic identity" when they abandoned Sumerian for Babylonian, and later the Babylonians and Assyrians likewise "disappeared as a people when they accepted the Aramaic language." Gelb adds that a similar process occurred with the spread of Arabic after the rise of Islam, so that language replacement often corresponds with the fading of earlier ethnic labels in surviving sources.

Taken at face value, Gelb's point is a clear language centred explanation for why names like "Assyrian" drop out of texts: when a population adopts a new vernacular, external observers and documentary traditions begin to call them by different names, and the older ethnonym recedes. This helps explain the apparent "disappearance" of ancient Assyrians from later historical narratives even where people, settlements and cultural practices continued in roughly the same places. Gelb is therefore arguing about how identity is recorded and remembered as much as about biological or cultural extinction.

That said, Gelb's formulation needs nuance if you use it as a description on a website. A shift of language does not automatically mean that a people vanishes in every meaningful sense. Families, religious institutions, local customs and claims of descent can and often do persist through language change. In other words, while the ancient label "Assyrian" may recede in written sources after an Aramaic takeover, communities with clear lines of continuity survived, and their descendants today may legitimately claim cultural, religious and historical connections to the older societies.

Ancient Iraq

George Roux writes that after the Medes and Babylonians destroyed Nineveh, Assyria disappeared almost overnight, its cities and culture vanished, unlike Babylonia, which the Persians did not destroy and where monuments and inscriptions show some continuity into later periods. In his words, Mesopotamian civilization lay buried and forgotten until modern excavations, and Assyria is among the Near Eastern states that were wiped out by devastating wars.

Assyria from the Earliest Times to the Fall of Nineveh

Smith traces Assyrian history from its beginnings to Nineveh’s fall in 612 BCE. Smith presents the Assyrians as a Semitic people in character and language, related to “the Jews, Syrians, and Arabs.” He stresses that Assyrian religion grew out of Babylonian religion, with the distinctive change of placing the city-god Assur at the head of the pantheon. In his narrative the empire’s rise rests on military vigor and centralized kingship under Assur.

For the end of the story, Smith writes that after Nineveh’s capture the land was divided among the conquerors: Egyptians held territory west of the Euphrates for a time, Babylonia took most of the country, and Media annexed the northern highlands. He concludes that Assyria then ceased to have a separate existence and was mostly absorbed into Babylonia; its cities decayed, its people dwindled, and its history and language were lost until modern excavations by Botta, Layard, Rawlinson, and others brought them back to light.

The Might That Was Assyria

Saggs describes ancient Assyria as a state that drew many different peoples into one system. From the 9th century BCE especially, Assyrian kings deported populations from conquered lands and settled them inside Assyria as Assyrians. Cities in the Assyrian heartland became “cosmopolitan and polyglot,” and Saggs adds that there is a real possibility that “people of actual ancient Assyrian descent were a minority” in those cities (p. 128). He notes that whole communities were relocated, new capitals were populated with deportees, and multiple languages were spoken in Assyrian towns.

For Saggs, identity rested not on blood, but on shared institutions. He titles a chapter “Assyrians: a Nation, Not a Race.” His blunt summary is: “The Assyrians were mongrels, and knew it. To them, ethnic purity was an irrelevance.” (p. 126). There were no laws enforcing ethnic separation; outsiders could rise to high office; newcomers often arrived and kept their group cohesion at first, yet over time they entered the Assyrian mix. He emphasizes that Assyrians did not define themselves as a tribe of common descent.

Religion and language were the primary social glue. The unifying language was Akkadian, and the central public cult was that of Ashur. Yet even here Saggs stresses flexibility: a person did not have to worship Ashur to belong in the administration, because the Assyrian pantheon could accommodate gods from other peoples. In plain terms, without Akkadian and the Ashur-centered state religion, there was no strong, single feature that bound everyone into one “ethnic” Assyrian people.

Saggs also looks back to the earliest periods and cautions against assuming a clearly bounded ethnic community from the start. He raises “the basic question about the very existence of an entity that we could call Assyria” in the mid–third millennium (p. 20). Across the second and first millennia, he traces repeated immigrations and deportations—Hurrian, Aramean, and others—that produced a long-term, mixed population in northern Mesopotamia; some districts later became predominantly Aramean. In his narrative, the countryside that survived the empire’s collapse was made up of villagers and peasants shaped by this mixed history, not a single, self-contained ethnic line.

Taken together, Saggs’ account presents ancient Assyria as a political and cultural umbrella rather than an ethnicity in the modern sense: a realm that intentionally integrated diverse groups, called them “Assyrians,” and held them together mainly through administration, Akkadian language, and the public cult of Ashur, with ethnic purity explicitly dismissed as irrelevant.