-

Title

-

Minority Identities Before and After Iraq

-

Creator

-

Yasmeen Hanoosh

-

Date

-

2016

-

Description

-

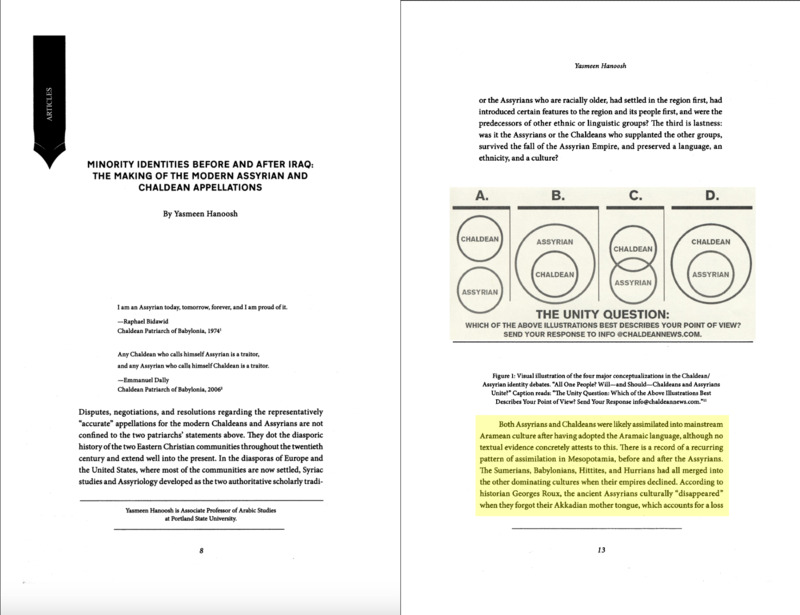

Yasmeen Hanoosh writes that the Chaldean–Assyrian identity dispute is not about whether people survived the fall of Nineveh. Some indigenous population clearly continued, and Aramaic persisted. What changes is how later communities tell a monumental history that links themselves to antiquity. In that long view, she argues, both Assyrians and Chaldeans were likely absorbed into mainstream Aramean culture after adopting the Aramaic language, much as other Mesopotamian empires had been absorbed when their own languages and polities declined.

Yasmeen Hanoosh writes that when missionaries and early excavators from the United States and Britain arrived in Mesopotamia in the early nineteenth century, they met East-Syriac Christians who variously identified as Jacobites, Nestorians, and Chaldeans and who also used the umbrella label “Syrian Christians.” This encounter helped set today’s name disputes in motion: the title “Assyrian” as a living communal label had not yet fully revived and only later came to supplant “Nestorian,” while “Chaldean” marked those who had accepted union with Rome.

She emphasizes that Western church patronage and great-power politics shaped communal lines as much as theology. Missionaries became conduits to foreign protection: some communities sought the Church of England’s backing, others aligned with the Roman Church and the French consulate. Conversions in this period were often strategic moves for security rather than changes of belief.

By the mid-nineteenth century these ties produced concrete administrative outcomes. In 1844 the French consul secured millet status for the Catholic Chaldeans; the following year, aided by Protestant missions, the Nestorians also obtained millet recognition. Their patriarch, Mar Shimun, now held both spiritual leadership and an Ottoman salaried office. In Hanoosh’s reading, the Anglo-American missionary presence, together with Catholic diplomacy, fixed the modern split between “Chaldean” and “Assyrian” and helped popularize the latter as the standard non-Catholic name.

Finally, Hanoosh traces the Church of the East from its Persian base to Baghdad, then its later dispersal and recurring succession crises. Papal diplomacy created a Chaldean patriarchate, while the remaining Nestorians later embraced the revived name Assyrian. Her conclusion is that today’s identities grew from hybrid inheritances shaped by language shift into Aramaic, assimilation to Aramean culture, and modern missionary and imperial naming, rather than from a single unbroken national line.

-

Language

-

English

-

Publisher

-

MINORITY IDENTITIES BEFORE AND AFTER IRAQ: THE MAKING OF THE MODERN ASSYRIAN AND CHALDEAN APPELLATIONS in The Arab Studies Journal, Vol. 24, No. 2, Yasmeen Hanoosh, p. 12–20.

-

jstor.org

-

Contributor

-

https://www.jstor.org/stable/44742878

image (4).png

image (4).png