assyrians

- Title

- assyrians

Items

Religious Origins of Nations?: The Christian communities of the Middle East

The author highest the fact that a connection to an Assyrian-Chaldean ancestry, as witnesses in the Chronicle of Saint Michael the Great, is only acknowledged in the use of a common language, i.e Aramaic and not an ethnic one. The author also confirms the fact that the tradition view of the Assyrians was presented in a negative and were not an ancestor the early Arameans would be proud of.

Oeuvre d'Orient

"During the Great War, the Nestorians sided with the Allies from the triumphant arrival of the Russian armies. The sufferings they endured from then on are well known. At the signing of the peace treaty, an Eastern Christian committee, composed of Catholics and non-Catholics, worked to obtain the creation of an independent Christian territory. This committee, like the proposed state, adopted the name “Assyro-Chaldean,” a new term that could be justified with a good definition, but which remained sufficiently vague to include all the Christians of the various Eastern rites in those regions, except the Armenians, who had particular historical and personal aims. The committee failed in its efforts, and in opposition to “Chaldean,” the Eastern Syrian Nestorians were called “Assyrians,” also a new term, which helped to confuse the concepts of many Europeans who were following, with interest, the minority question in the East, even from a strictly Catholic point of view; this term allowed absolutely erroneous official statements by certain important and necessarily well-informed figures."

The author describes the Nestorians, an Eastern Christian population long based in the Hakkari mountains between Lake Van and Lake Urmia. They lived under Ottoman rule but dealt directly through their patriarch Mar Shimun and were influenced by Russia as well as by Dominican and Anglican missions. Over the centuries some communities reunited with Rome and became Chaldeans, a Catholic church with its own patriarch and bishops; the author says most Iraqi Catholics belonged to this group and estimates roughly sixty to eighty thousand at the time.

During and after the First World War a mixed Eastern Christian committee tried to obtain an independent Christian territory. For this project it adopted the new umbrella label “Assyro-Chaldean,” which the author calls vague enough to cover many Eastern Christian groups in the region except the Armenians, and the effort failed. In the same period the Eastern Syrian Nestorians began to be called “Assyrians,” another new label. The author argues that these terms led Western observers, diplomats, and even churchmen to confuse identities and make erroneous official claims. He adds that there were about sixty thousand Nestorians worldwide then (not counting the Indian Nestorians), around thirty thousand of whom were in Iraq until 1933. A League of Nations mission in 1924 examined their case but promised solutions did not materialize, and after the 1933 crisis with Iraq many among them wished to leave for Syria. The overall message is that the recent political and ecclesiastical names “Assyro-Chaldean” and “Assyrian” blurred distinctions among Eastern Christians and generated misunderstanding in European and official discourse.

Assyrian Ethnicity in Chicago

“Assyrians today may be Kurds, Turks, etc., with little possibility that these people have some of the ancient Assyrian blood-lines.”

“The Assyrians of today are not related to the ancient Assyrians at all—racially, ethnically, nor historically.” (cited by May Abraham from Dr. Kretkoff)

According to May Abraham’s pages (drawing on Ignace Gelb and John Joseph), the ancient Assyrian language had died out while the communities in question spoke Aramaic/Syriac; Joseph argues that today’s “Assyrians” are using the wrong name, should call themselves Chaldeans, and that what is called modern Assyrian should be called Aramaic. In this framing, “Assyrian” in the U.S. context functioned as an umbrella category that grouped Chaldeans, Jacobites, and members of the Church of the East from Iraq, Syria, Iran, Turkey, Kuwait, and Lebanon, who also used multiple everyday languages. Abraham underscores the point with two explicit claims from the text: “Assyrians today may be Kurds, Turks, etc., with little possibility that these people have some of the ancient Assyrian blood-lines,” and “The Assyrians of today are not related to the ancient Assyrians at all—racially, ethnically, nor historically” (cited by May Abraham from Dr. Kretkoff). Taken together, these statements present “Assyrian” as a modern, label-driven umbrella rather than a biologically or historically continuous identity from antiquity.

The Legacy of Mesopotamia

Stephanie Dalley writes that Syriac Christians from northern Iraq sometimes give their sons names like Sennacherib or Sargon and consciously identify with the ancient Assyrians, calling themselves “Assyrians” (Athoraye) rather than “Syriacs” (Suraye). She says this identification was fostered by Anglican missionaries working with the Nestorian Church in the nineteenth century and was later encouraged by the British in the late 1940s.

The Nestorian Churches: A Concise History of Nestorian Christianity in Asia From the Persian Schism to the Modern Assyrians

Aubrey R. Vine writes that British contact with the East Syriac Nestorians quickened after C. J. Rich’s encounters near Nineveh in the 1820s. Rev. Joseph Wolff carried a Syriac New Testament to England, and the British and Foreign Bible Society printed and distributed it around Urmi in 1827, while European governments protested after Kurdish attacks in 1830. The American Presbyterians opened a long mission at Urmi, while the Church of England worked through the SPCK, sending Ainsworth and later George Percy Badger, who earned goodwill by offering aid without trying to change doctrine and who sheltered the patriarch during the 1842 massacres. After the Nestorians appealed to Archbishop Tait in 1868, E. L. Cutts’s inquiry led to the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Mission to the Assyrian Christians in 1881, staffed by Rudolph Wahl, later Canon Maclean, Athelstan Riley, W. H. Browne, and finally Canon W. A. Wigram. The mission lasted until the Great War and moved its headquarters from Urmi to Van in 1903.

Vine explains that late 19th century Anglicans deliberately adopted “Assyrian” as the title for their mission among the East Syriac Nestorians. The Archbishop of Canterbury’s Mission used it in reports, school charters, and correspondence, and the term soon spread into wider English usage, so that newspapers, missionary journals, and general readers spoke of Assyrian Christians rather than Nestorians. The choice was both strategic and pastoral: it emphasized the community’s rootedness in the old Assyrian heartland, and it avoided the polemical associations of “Nestorian,” a term long tied to heresy and theological controversy. The new name also gave the community a dignified ethnonym that Western audiences could respect, while allowing Anglicans to support and reform the church without reopening ancient doctrinal debates.

Vine further notes that the community did not historically call itself Assyrian. In earlier Greek, Latin, and Western sources it was very often referred to as the Persian Church, because its catholicoi resided at Seleucia-Ctesiphon in the Sasanian Persian Empire, and its jurisdictions extended deep into Persia and beyond. Its own traditional title was the Church of the East, using the East Syriac rite and language. In Vine’s account, therefore, “Assyrian” was a modern, mission-driven designation, introduced and popularized by Anglicans, which gained legitimacy through long usage and was later embraced by many within the community itself, culminating in the modern name Assyrian Church of the East.

A Religious Encyclopedia

Philip Schaff (ed.) in A Religious Encyclopædia (1891), article “Semitic Languages,” states that “the Babylonian-Assyrian disappeared from history in the sixth century B.C., and their language survived only a few centuries,” whereas “the Syriac-Arameans lost their independence in the eighth century B.C., but continued to exist, and their dialect revived in the second century A.D. as a Christian language; and the Jewish Aramaic continued for some centuries (up to the eleventh century A.D.) to be the spoken and literary tongue of the Palestinian and Babylonian Jews.” In other words, as Schaff’s encyclopedia writes, the Assyrian-Babylonian tradition faded early as a historical nationality and language, while the Arameans lived on through enduring Christian and Jewish Aramaic traditions.

Fatal Ambivalence: Missionaries in Ottoman Kurdistan, 1839-43

Jessica R. Eber notes that the communities often linked with the “Church of the East” have been described by outsiders with several names over time, among them Syrian (referring to the liturgical language), Assyrian, Assyro-Chaldean, Old East Syrian Church, and Apostolic Assyrian Church of the East. She explains that Protestant missionaries popularized the label “Nestorian” to distinguish these Christians from the Chaldeans who entered communion with Rome in the fifteenth century. Eber also cautions against equating these communities directly with the Assyrians of the Old Testament, calling that linkage an inaccurate assumption that nevertheless influenced some nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholarship. Today, she observes, the term “Nestorian” is sensitive and often avoided, since many Christians use it pejoratively to denote schism or heresy.

Ethnic Realities and the Church: Lessons from Kurdistan : a Historical Study of Missionary Work, 1668-1990

Blincoe writes that in the 19th century Anglican missionaries promoted the name “Assyrian” for members of the Church of the East who did not join the Roman Catholic communion. They saw it as a less pejorative alternative to “Nestorian.” Earlier labels such as “Chaldean” for those in communion with Rome and “Nestorian” for those who were not referred mainly to church affiliation and geography, not to ancient ethnic descent. Blincoe concludes that modern Assyrians and Chaldeans should not be regarded as direct descendants of the ancient Assyrians or Chaldeans.

The Development of Harvard University Since the Inauguration of President Eliot 1869–1929

David G. Lyon, Hancock Professor of Hebrew and Other Oriental Languages at Harvard, states that among the ancient Semitic peoples of Western Asia (Arabs, Arameans, Assyrians, Babylonians, Hebrews/Jews, Phoenicians; and in Africa, Ethiopians), the Babylonians and the Assyrians had “vanished long since.” He contrasts this with the modern scholarly recovery of their languages and literary treasures. Notably, Arameans are listed but not said to have vanished, underscoring a distinction Lyon draws between groups that disappeared as historical nations and those that did not.

The Concise Encyclopedia of Archaeology

Leonard Cottrell’s edited volume The Concise Encyclopedia of Archaeology, a collaborative work by 48 contributing scholars specializing in history and languages, explains that Assyrian power ended catastrophically with the sack of Nineveh in 612 BC. From that point, the Assyrians “disappeared as a nation for ever.” The entry adds that their modern image is mediated largely through Old Testament narratives and, more recently, through the decipherment of their own inscriptions, while emphasizing that no Assyrian nation survived beyond the seventh century BC.

The Stones Cry Out

Randall Price contrasts biblical prophecies about Babylon’s permanent desolation with Nineveh’s fate. He notes that Scripture does not predict that no one would ever live at Nineveh again; in fact, the site is inhabited today, but not by Assyrians. What was foretold, he stresses, is that the Assyrians themselves would vanish and that the city would never be rebuilt as a functioning capital. Price therefore distinguishes between later settlement on the mounds and the absence of a restored Assyrian people or a revived Nineveh.

The Ancient History of the Near East: From the Earliest Times to the Battle of Salamis

H. R. Hall explains Assyria’s collapse as a combination of military exhaustion and institutional fragility. Already under Sennacherib, he notes, the army had to be filled with subject peoples, which degraded its quality. By Ashurbanipal’s later years only a shadow of the old Assyrian fighting force remained. Hall speaks of the “degeneracy and disappearance of the army,” and because “the army was the nation,” the degeneracy and disappearance of the nation followed. When Nineveh fell, he writes, “literally the Assyrian nation was destroyed.” Unlike Babylon and Thebes, which were destroyed but revived their national life, Assyria “never rose again,” because no peace-organization or proper civil system existed to hold the realm together. The successors of Tiglath-pileser IV, in his view, lacked the intelligence to develop a lasting administrative structure; Assyria had become almost purely a military machine, whereas Egypt and Babylonia possessed age-long civil administrations that could outlive foreign rule.

Dictionary of the Bible

John L. McKenzie’s entry “Assyria” sketches both the empire’s rise and its abrupt extinction. He says the collapse followed the death of Ashurbanipal: after a century of almost continuous warfare Assyria had exhausted its manpower, while new forces gathered on its borders—the Medes and Scythians to the north and Chaldeans in the south. In 612 B.C. Nineveh was stormed and thoroughly destroyed; its cities, he notes, were so completely ruined that they were never rebuilt. A last Assyrian remnant under Ashur-uballit attempted to carry on from Harran with Egyptian help, but the final blow came when the Babylonians and their allies crushed them at Carchemish in 605 B.C., after which, McKenzie concludes, “the Assyrians disappeared from history.”

Western Society: A Brief History

John P. McKay and coauthors explain that after the joint Median and Babylonian assaults of the late seventh century BCE, Assyrian urban centers were destroyed and imperial power collapsed. With their cities in ruins and political authority gone, the Assyrians “disappeared from history,” surviving mainly as a negative memory in biblical tradition. They add that about two centuries later Xenophon marched past the mounds of Nineveh without recognizing them, illustrating how completely the imperial past had faded from living knowledge until modern rediscovery.

The New Answers Book 1

In The New Answers Book 1 (2006), Ken Ham includes a sidebar titled “Does Archaeology Support the Bible?” that lists historical notes related to Assyria. One point claims that as the Assyrians “disappeared from history after the Battle of Carchemish in 605 BC,” the Bible’s retention of specific Assyrian titles (e.g., rabmag, rabshakeh, tiphsar) supports the texts’ authenticity, since such “obsolete” terms would have been preserved by eyewitness writers.

Freedom in the Ancient World

Herbert J. Muller frames the fall of Nineveh as a civilizational rupture. He writes that when the capital was “utterly destroyed” and the Assyrian kingdom “extinguished,” the Assyrians disappeared from history with unusual speed—“more quickly than any other prominent people before or after them.” In his narrative, what follows is a brief Chaldean interlude, but the obliteration of Assyria was so complete that even by Xenophon’s day the ruins passed unrecognized. Muller’s point is not just political collapse; it’s cultural erasure, the Assyrian name and memory slip from the lived historical record, leaving only later rediscoveries to reconstruct what had been the most feared power of the Near East.

Mosul and Its Minorities

Sir Harry Charles Luke uses Mosul’s annual Fast of Nineveh to contrast a living memory with an obliterated past. He writes that apart from this fast and a few earthen mounds, there are no visible links between modern Nineveh and the terror-inspiring city of antiquity. The destruction of Nineveh in 608 BC by the Medes and Babylonians, he says, was so complete that within a single lifetime the Assyrian Empire had not merely fallen but vanished from the face of the earth. Two centuries later, Xenophon marched past its ruins without recognizing that they were the remains of the former imperial capital. Luke adds that, with rare exceptions, the fearsome Assyrian monarchs had been forgotten by the very people who later lived on the site. In his depiction, what survived in Mosul was a religious observance and archaeological remnants, not a continuing Assyrian people.

The Cradle of Mankind: Life in Eastern Kurdistan

W. A. Wigram describes the ruins of Nineveh and recounts the city’s final overthrow by Median and Babylonian forces. He writes that the Assyrian dynasty perished in flames in its own palace and concludes that after Nineveh fell there were no true Assyrians left, only a half-bred remnant produced by incessant intermarriage, scattered and incapable of recovery. He emphasizes that what remained at the site were walls, moats, and buried palaces rather than a continuing Assyrian people.

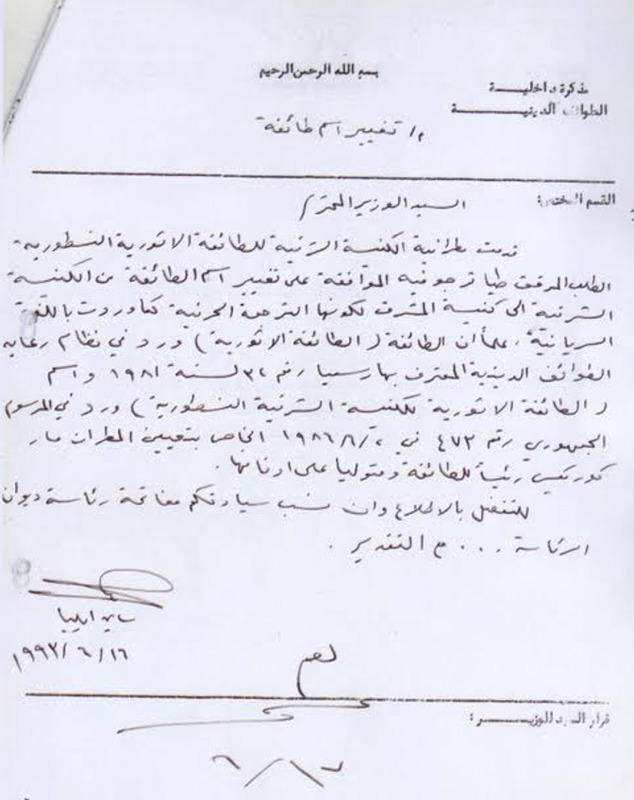

A Request to the Ba'ath Authorities

In 1993, leaders of the Ancient Church of the East in Iraq petitioned the Ba’ath authorities to register the church simply as the Church of the East rather than Ancient Eastern Church, presenting the change as a confessional designation and explicitly distancing it from an ethnic label.

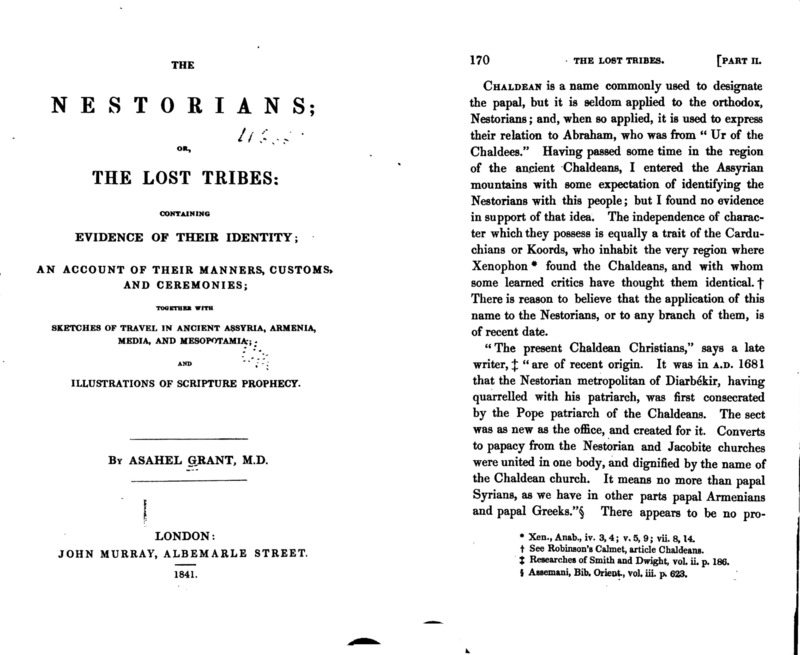

The Nestorians; or, The Lost Tribes

Asahel Grant set out expressly to explore the Assyrian mountains to test the claim that the Nestorians were direct descendants of the ancient Assyrians, and after on the ground inquiry he says he found no evidence for that identification. Asahel Grant was an American physician and traveler who journeyed through northern Mesopotamia and into what he called the Assyrian mountains. He approached the region with the then popular expectation of linking the contemporary Nestorians to peoples of antiquity. After spending time in the country of the ancient Chaldeans, he explicitly states that he found no evidence to support such identifications. In particular, he argues that the ecclesiastical title “Chaldean” when applied to East Syriac Christians is of recent origin, arising in 1681 when a Nestorian prelate at Diyarbakir entered communion with Rome and was consecrated as patriarch of the Chaldeans. Grant describes this as the creation of a new Catholic body of “papal Syrians,” comparable to papal Armenians or papal Greeks. From his on the ground observations he treats the nineteenth century ethnonyms being applied in the area, including “Assyrian” and “Chaldean,” as modern overlays rather than proof of direct descent from the empires of antiquity, despite his own travel focus on the Assyrian districts and his interest in ancient Assyria.

Syrisch-orthodoxen, nestorianen en Assyriërs

According to this 1993 interview in Reformatorisch Dagblad, Prof. L. van Rompay (Leiden) explains that the Syriac Orthodox in southeast Turkey can be seen both as a religious and an ethnic minority: they have their own church and a distinct national-cultural identity, neither Turkish nor Kurdish, and are largely descended from the old populations of Mesopotamia. He sketches the late-antique church landscape in which Aramaic/Syriac-speaking communities formed on both the Roman and Persian sides. Christological disputes in the fifth–sixth centuries produced parallel traditions: the East-Syrian/Nestorian Church in the north of present-day Iraq and the Syriac Orthodox (often called “Monophysites”) in what is now southern Turkey. The Nestorian Church emphasized a clear distinction of Christ’s two natures and was condemned at Ephesus (431). The Syriac Orthodox tradition arose from resistance to Chalcedon (451), affirming one united divine-human nature; its patriarch later settled in Damascus, with communities across Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Europe, and the Americas.

Dr. Heleen Murre-van den Berg adds that the label “Assyrians” for Christians of northern Iraq and southeast Turkey applies mainly to the Nestorians/East Syrians and is of fairly recent origin, dating from the late nineteenth century. American and British missionaries built schools and introduced the first printing press, fostering cultural consciousness. At the same time, excavations of ancient Nineveh encouraged some Nestorians to link themselves to the ancient Assyrians and to articulate a national program (“we are one people; we should restore the Assyrian kingdom”). Syriac Orthodox Christians largely kept their distance from this project. Van Rompay concludes that while cultural continuities with ancient Mesopotamia exist, the Assyrians of antiquity were assimilated into many peoples over time; therefore no direct line can be drawn from the ancient Assyrians to today’s Nestorians, even if modern groups adopt the Assyrian name in a symbolic sense.

Christian Science Monitor

A short Christian Science Monitor note from September 1953 comments on mid-century terminology for East Syriac Christian refugees. It states that “Assyrian” was being used as a misapplied label that arose after World War I, when survivors of the Ottoman-era massacres fled to Iraq and were assisted under a League of Nations trusteeship supported by Britain, Iraq, and the League. The piece situates the naming issue within contemporary discussions of funding and politics surrounding refugee aid and associated publications.

Assyrian Christians

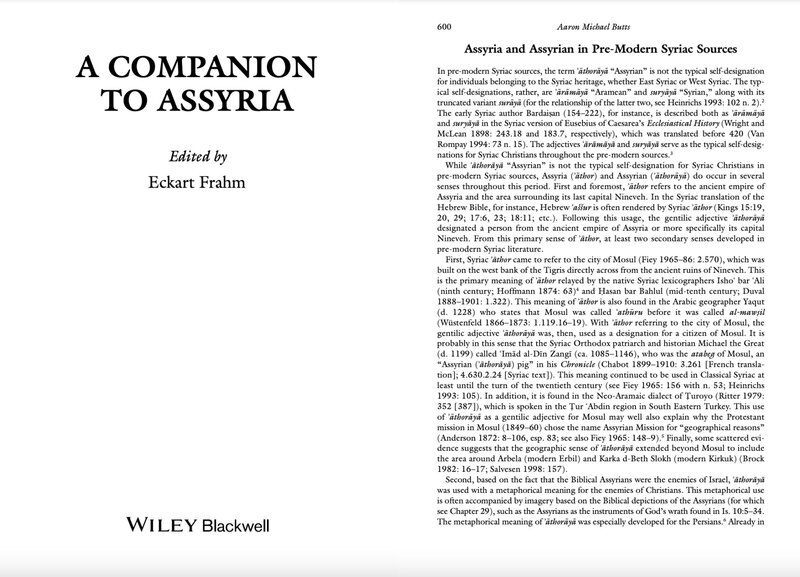

According to Aaron Michael Butts, pre-modern Syriac sources do not use “Assyrian” as a normal self-designation for Syriac Christians. The typical self-labels are Oromoyo (“Aramean”) and Suryaya/Suryoyo (“Syriac”), with Suryaya becoming the standard adjective for Syriac Christians across the period. By contrast, Assyria/Assyrian (Othur / Othuroyo) appears in two other senses: first, the biblical–historical meaning referring to the ancient empire and to places like Nineveh; and second, a geographical gentilic used locally, above all for people from Mosul and, by extension in some texts, the region around Arbela (Erbil/Kirkuk). A further, purely rhetorical use appears in Christian writing where “Assyrians” function metaphorically as enemies of Israel, echoing biblical imagery rather than communal self-naming.

Butts then traces how “Assyrian” became attached to Syriac Christians in nineteenth-century Western literature. Early travelers occasionally wrote “Assyrian Christians” merely to mean Christians in Assyria (e.g., C. J. Rich), and some outsiders (Armenians) used forms like Asouri for them. The tighter linkage of East-Syriac Christians with ancient Assyria was popularized by A. H. Layard, who argued they were the descendants of the ancient Assyrians—though he did not claim the communities called themselves Assyrian. The systematic use of “Assyrian” for these Christians developed in the second half of the nineteenth century around the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Mission in Urmia. Seeking an alternative to the stigmatized term “Nestorian” (and distinct from “Chaldean” for the Roman-Catholic branch), Anglican writers adopted “Assyrian”; by 1870 the term was entrenched in Anglican vocabulary, and the mission’s official name became “The Archbishop of Canterbury’s Mission to the Assyrian Christians.” From there it spread in the West, even if field missionaries did not all use it consistently at first. The upshot in Butts’s chapter is that “Assyrian” as a communal label for Syriac Christians is modern and externally driven, arising from nineteenth-century Western (especially Anglican) discourse rather than from pre-modern Syriac self-designation.

Revival and Awakening: American Evangelical Missionaries in Iran and the Origins of Assyrian Nationalism

Becker argues that the modern ethnoreligious use of “Assyrian” is an “invented tradition”—a revived ancient appellation taken up in the nineteenth–twentieth centuries from Western scholarly and missionary discourse, not from an unbroken continuity with the ancient Assyrians. European and American missionaries, diplomats, and archaeologists routinely used “Chaldean” and “Assyrian” for East-Syriac Christians in and around Urmia and upper Mesopotamia; that external usage, he says, was gradually appropriated by the East Syriac community itself.

Becker’s aim is to explain how and why this retrieval succeeded. He locates the key drivers in the East Syrians’ intensive engagement with American evangelical missionaries, coupled with language reform, autoethnographic writing, and the push for a national literature—processes that made a modern national identity both imaginable and compelling. The result, in his account, is a self-consciously modern Assyrian identity whose label derives primarily from Western sources, but whose adoption was enabled by local social and ideological dynamics.

Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World

Crone and Cook argue that Syrian Christians (Suryane) moved from an older ethnic frame to a primarily religious one: as Christianity reordered communal life around baptism and Eucharist, “Aramean” came to be associated with a defeated pagan past and was relinquished as an ethnic badge, even though the word survived in usage (especially for language). In a note they add that the Suryane of Nestorian Iraq “quite frequently speak of themselves and their language as Aramean.” By contrast, pagan Harranians kept “Aramean” precisely by binding it to their native cult, maintaining a nation-plus-religion identity and hopes of restoring an earthly polity.

The later trajectory of these East-Syrian Iraqis aligns with the modern naming shift documented elsewhere in your sources: from the nineteenth century, Western missionaries and writers popularized “Assyrian” for the non-Catholic heirs of the Church of the East, and by the early twentieth century many descendants of those Iraqi communities publicly identified as Assyrian.

Making History to/as the Main Pillar of Identity: The Assyrian Paradigm

In Making History To/As the Main Pillar of Identity: The Assyrian Paradigm, Bülent Özdemir explains that the English term “Assyrian” has shifted meaning over time and across institutions, creating persistent confusion. In academic English it often points to the ancient Assyrians of Assur, but nineteenth-century Protestant missionaries began applying it loosely to a range of Eastern Christian communities, including—misleadingly—some labeled “Nestorian.” During and after World War I the British army continued this loose usage, even naming mountain Nestorian auxiliaries the “Assyrian Levies.” Meanwhile, “Syrian/Syriac Christian” in English can cover several Eastern churches (usually not the so-called Nestorians) and is defined inconsistently by different writers; in Turkish and Arabic, Süryani denotes Syrian Christians and is sometimes extended to Nestorians. Özdemir also notes that some modern Eastern Christian nationalists use “Assyrian” as a notional ethnonym for political purposes.

Inledning till studiet av det assyriska folkmordet

In Inledning till studiet av det assyriska folkmordet (translation), David Gaunt argues that research on the Assyrian genocide is riddled with terminological pitfalls rooted in how identities were recorded. Under the Ottoman millet system, subjects were classified by religion rather than ethnicity, so ethnic labels like “Assyrian” are largely absent from official sources. Instead, Syriac Orthodox communities appear as Süryani or Yakubiler (from Jacob Baradeus), Chaldean Catholics as Keldani, and members of the Church of the East as Nasturiler—labels echoed in older ecclesiastical discourse as “Jacobites” and “Nestorians.” Neighboring and later traditions added their own exonyms: Armenians called these groups aisori (a term that entered Russian), while late-nineteenth-century Anglo-Saxon missionaries popularized “Assyrian,” typically referring chiefly to the Church of the East; many American and German sources, by contrast, used the umbrella “Syriacs.”

For Gaunt, the consequence is methodological: the same people can surface in archives under different names depending on the language, confessional lens, or missionary agenda of the source. Effective scholarship therefore requires “cross-walking” these labels across Ottoman Turkish, Armenian, Russian, German, and English materials, attending to transliteration variants and the confessional baggage each term carries, and recognizing that “Assyrian” gained broader ethnonymic currency relatively late.

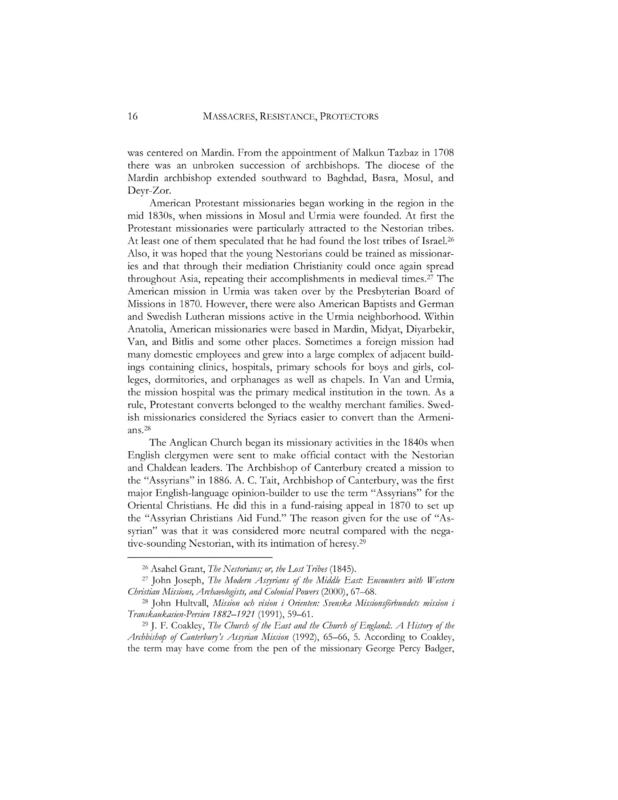

Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia during World War I

In Massacres, Resistance, Protectors (2006), David Gaunt explains that Anglican work in the mid nineteenth century helped standardize “Assyrian” as a label for Eastern or “Oriental” Christians, especially those often called Nestorians. English clergy began formal contacts in the 1840s, and in 1870 Archbishop A. C. Tait used “Assyrians” in a public appeal to establish the Assyrian Christians Aid Fund. In 1886 the Archbishop of Canterbury created a mission explicitly to the Assyrians. Gaunt notes that the choice of “Assyrian” was deliberate, since it sounded neutral and dignified compared with “Nestorian,” a term burdened by charges of heresy. Through Anglican fundraising, reports, and mission networks, this usage spread in English discourse and helped shift a confessional label toward a broader ethnonym.

De kristna i Mellanöstern: slutet på en tvåtusenårig historia?

Ingmar Karlsson writes that Sweden’s Liberal Party believed it was championing the extinct Assyrian people and Middle Eastern Christians, but in practice its efforts concerned Syriac Orthodox Christians specifically, one of the smallest of the many churches in the region.

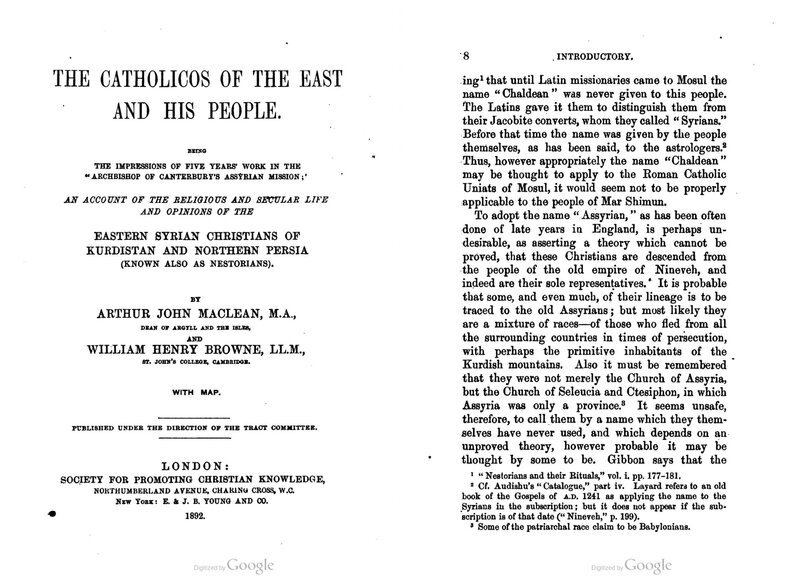

The Catholicos of the East and His People

Maclean and Browne report that the modern Assyrians habitually call themselves Syriacs or Suryayi (Surayi), and in formal documents “The Church of the East” or simply “The Easterns.” They rarely call themselves “Nestorians,” and resent it when used as a nickname. The authors stress that “Syrian” functions as a religious label shared with the Jacobites, not a racial or national term. They note that in England a fashion had lately arisen to use “Assyrian,” partly to distinguish these Christians from the Jacobites and partly from the supposition that they descend from the ancient subjects of Shalmaneser and Sardanapalus; they judge this usage unsafe and undesirable because the people themselves never used it, their lineage is mixed, and Assyria was only one province within the wider realm of the Church of Seleucia and Ctesiphon. They go further to argue that the modern Assyrians are most likely a mix of races, probably including Kurds, and that the claim of direct descent from the ancient Assyrians is unproven, with writers often confusing the people with the Assyrian Empire itself. They add that none of the territory inhabited by modern Assyrians can properly be called Assyria and that maps sometimes misassign the Kurdish mountains to it.

On “Chaldean,” they write that the name was never given to this people until Latin missionaries came to Mosul; the Latins applied it to distinguish their Roman Catholic converts from the Jacobites, whom they continued to call “Syrians.” In the community’s own old books, “Chaldeans” had meant astrologers, against whom they bore old enmity, so the authors conclude the title properly belongs to the Roman Catholic Uniats of Mosul, not to the modern Assyrians.

They further warn of recurrent confusion in learned and popular writing, citing the tendency for “Nestorians … under the name of Chaldeans or Assyrians” to be confounded with the most learned or the most powerful nation of Eastern antiquity. To avoid ambiguity, the authors themselves prefer “Syrians,” and when a distinction from the Jacobites is needed, “Eastern Syrians.”

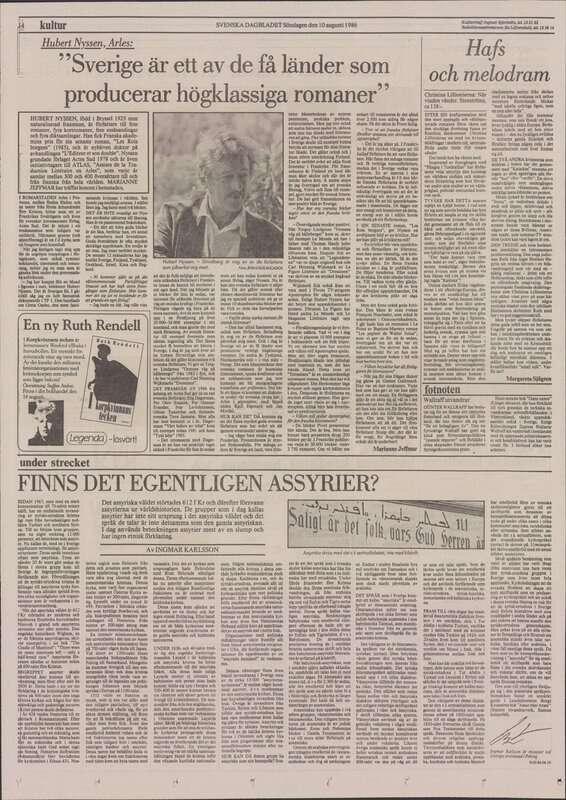

Are there really Assyrians?

The article “Finns det egentligen assyrier?” (“Do Assyrians Really Exist?”) by Ingmar Karlsson examines the question of whether the modern people who call themselves Assyrians are in fact descendants of the ancient Assyrians of Mesopotamia, or whether the name represents a more recent historical and cultural construction.

Karlsson begins by outlining the background of the modern Assyrian movement in Sweden, which gained strength in the 1970s when immigrants from southeastern Turkey and northern Syria began identifying themselves as Assyrians. He explains that the ancient Assyrian Empire was destroyed in 612 BCE, and with its fall, the Assyrians disappeared from history as a political and ethnic entity. The groups that today call themselves Assyrians, he argues, do not originate from that ancient population. Instead, they descend from Syriac-speaking Christian communities that emerged centuries later in Mesopotamia. These Christians, who belonged to what became the Syriac Orthodox and Chaldean Catholic churches, spoke Aramaic rather than the ancient Assyrian language.

The article emphasizes that the designation “Assyrian” has no direct ethnic continuity with the Assyrian Empire. Karlsson notes that the use of the term in modern times is mostly coincidental, a result of later historical developments and church traditions rather than of an unbroken ethnic lineage. He traces the evolution of these Christian communities, describing how the Church of the East, the Chaldeans, and the Syriac Orthodox Church all developed from early Mesopotamian Christianity. Over time, the Syriac language replaced earlier local tongues and became a major liturgical language in the region.

Linguistically, Karlsson stresses that the modern Assyrian or “Syriac” language spoken today is not derived from the ancient Assyrian tongue but from Aramaic. The ancient Assyrian cuneiform script and its Semitic language vanished long before the birth of Christ. Modern Assyrians speak various Neo-Aramaic dialects that have been heavily influenced by Arabic and other regional languages. He further notes that the term “Assyrian” gained new meaning in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as part of a nationalist revival among Syriac-speaking Christians. This revival, particularly in the diaspora, sought to unite different Syriac Christian groups under a common historical label, using the name “Assyrian” to evoke the grandeur of the ancient empire and to assert continuity and identity in modern times.

Karlsson concludes that the modern Assyrians are not ethnically descended from the ancient Assyrians. Instead, they are the cultural and religious heirs of ancient Mesopotamian Christianity who adopted the Assyrian name as a historical and symbolic identity rather than an ethnic one. For him, “Assyrian” today is a cultural and ecclesiastical designation used to express unity and heritage, not a literal continuation of an ancient people.

The Lesser Eastern Churches

Fortescue argues that the proper technical name for Mar Shimun’s flock is “Nestorians,” the term used universally since the fifth century and one they themselves have often accepted in devotion to “the Blessed Nestorius.” He criticizes the growing Anglican habit of avoiding “Nestorian,” insisting the label need not imply agreement with the condemned heresy and that the group was not founded by Nestorius in any case. Alternative labels fare no better: “Persian Church” or “Turkish Church” are vague; “East Syrian Church” is closer, but too imprecise because there are many different East Syrian bodies.

He reserves particular disdain for the newly adopted “Assyrian Church,” calling it “the worst of all.” In his view they are “Assyrians in no possible sense.” The people inhabit only a corner of the territory once ruled by the Assyrian Empire, a land also covered by the Babylonian Empire; if one follows that logic, he quips, why not call them the “Babylonian Church”? On descent, he says no one can specify the mixture of blood in these lands; while some Nestorians may carry the blood of old Assyrian subjects, so do many other Mesopotamian sects. The empire itself ended centuries before Christ, so a tiny modern sect cannot inherit the name of the vast, long-vanished state. For Fortescue, “Assyrian Church” is neither old, accepted, nor common; it is a recent fad among a handful of Anglican sympathizers.

On “Chaldean,” he explains that this title belongs to the Uniate body corresponding to the Nestorians. Although the word is not ideal, it is fixed by universal and official usage at Rome: they call themselves Chaldeans; their liturgical book is the Missale chaldaicum; and their head bears the style Patriarcha Babylonensis Chaldaeorum. Hence, for the Catholic Uniate counterpart he prefers “Chaldean,” while for Mar Shimun’s non-Uniate community he retains “Nestorian,” and, when a broader confessionally neutral term is needed, “East Syrian.”

Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923

Frazee situates the naming issue inside a concrete 19th-century history of the Church of the East and the emerging Chaldean Catholic hierarchy. He recounts the Roman attempt to stabilize the Mosul area by recognizing Yuhanna Hormizd as Chaldean catholicos in Mosul while approving Rabban Hormizd monastery’s constitution under Jibra’il Denbo. Tensions followed: Bishop Yusuf Audo of Mosul was shifted to Al-‘Amadiyah; two apostolic visitors were dispatched to reconcile factions; and in May 1832 Denbo and two companions were cut down by Kurdish raiders. Rome then kept a close watch by establishing a permanent Latin apostolic vicarage in Mosul. When Patriarch Yuhanna resigned shortly before his death on 16 August 1838, the synod chose Niqula Zaya, whom Rome confirmed in April 1840, though he insisted on residing in his Persian see.

Within that setting, Frazee describes how the ethnonym “Assyrian” entered Western usage. In 1820 James Rich of the British East India Company proclaimed he had discovered “Assyrian Christians,” and Europeans adopted the label for the Church of the East—eventually some community members did so too. Frazee calls this an unfortunate addition to the already misleading Catholic title “Chaldean,” producing a pair of confusing names for related but distinct bodies. He notes the influx of British and American missionaries who distributed Bibles and catechisms and tried to explain doctrine to local audiences. One consequence he judges positive was new public attention to the vulnerability of these Christians to Kurdish depredations. He cites the American Presbyterian Eli Smith’s encounter at Khosrowa with a Chaldean bishop, an elderly man in a long Kurdish cape, green turban, and ragged sheepskin pelisse, whose poverty was striking despite a Roman education and some familiarity with the West.

The Syriacs of Turkey: A Religious Community on the Path of Recognition

Erol explains that the Christians long labeled “Nestorians” in church polemics, later called Assyrians in Western usage, are the Church of the East, whose Christology was condemned at Ephesus in 431. He situates them among Jacobite villages north of Mosul (notably Telkayf) and describes their settlement in the Tiyari and Hakkari regions, organized as independent tribal groupings.

He then traces the modern ethnic project that gathered different Syriac Christian streams under an Assyrian banner. After arriving in the United States in 1916, Naum Faik changed his own identification and called on “Nestorians, Chaldeans, Maronites, Catholics, and Protestants” to remember their shared past, blood, and language, to exalt the name of the Assyrians, and to unite to secure Assyrian rights.

Hostages in the homeland, orphans in the diaspora : identity discourses among the Assyrian/Syriac elites in the European diaspora

Atto explains that these communities historically self-named in their own Aramaic as Suroye/Suryoye (modern/classical Syriac). Neighbors called them Suryani (Arabic, Kurdish) and Süryaniler (Turkish). Western scholars long translated Suryoye as “Syrians,” a rendering many Assyrian and Syriac elites rejected because it confused them with the citizens of Syria. To avoid that confusion, elites in the late Ottoman and early American contexts promoted “Assyrian.” Atto cites Naum Faik (1916) urging readers of Bethnahrin in America to adopt the national label Assyrian in English, precisely to distinguish themselves from “Syrians.”

Atto frames this within a broader name debate. In diaspora settings, elites first insisted they were not Turks, Arabs, or Kurds; then many stated they were not Othuroye (Assyrians) but Suryoye; later, the alternative label was articulated as Syrianer or Arameans. Choosing Assyrian in Europe and the United States, she argues, “kills two birds with one stone”: it prevents confusion with Syrians and signals a distinct national identity among immigrant minorities. Young, secular elites advanced this usage, anchoring claims for international recognition as a people with cultural, linguistic, and religious rights.

National and Social Identity Construction among the Modern Assyrians/Syrians

Woźniak-Bobińska writes that the label “Assyrians” generates persistent confusion because names and identities don’t always map onto each other. Up to the 19th century, people in these communities primarily called themselves Suryoye/Suryaye. The term “Assyrians” was popularized mainly by Western researchers, while contemporary scholars often prefer “Syrians” or “Arameans.” Within the churches, members of the Syriac Orthodox call themselves mostly “Syrians/Syriacs,” and followers of the Chaldean Catholic Church prefer “Chaldeans.”

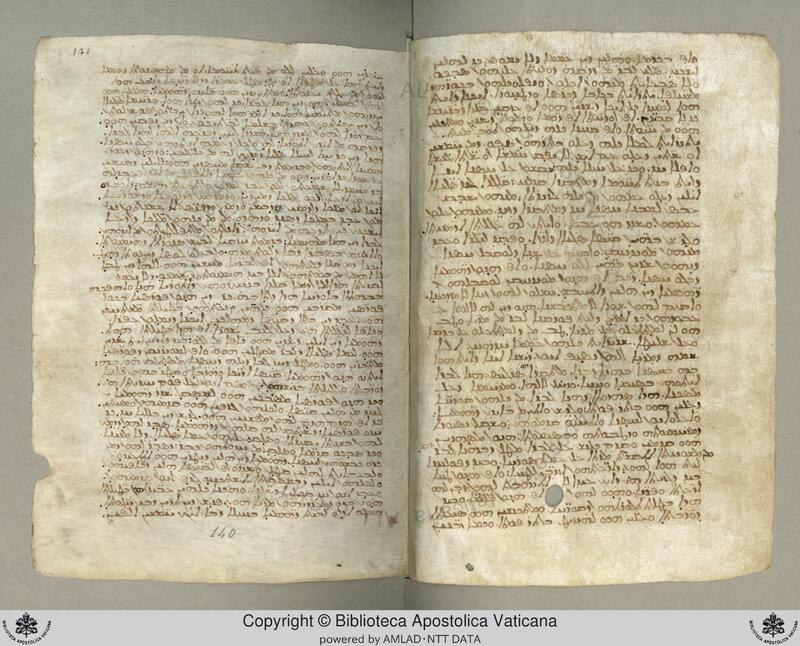

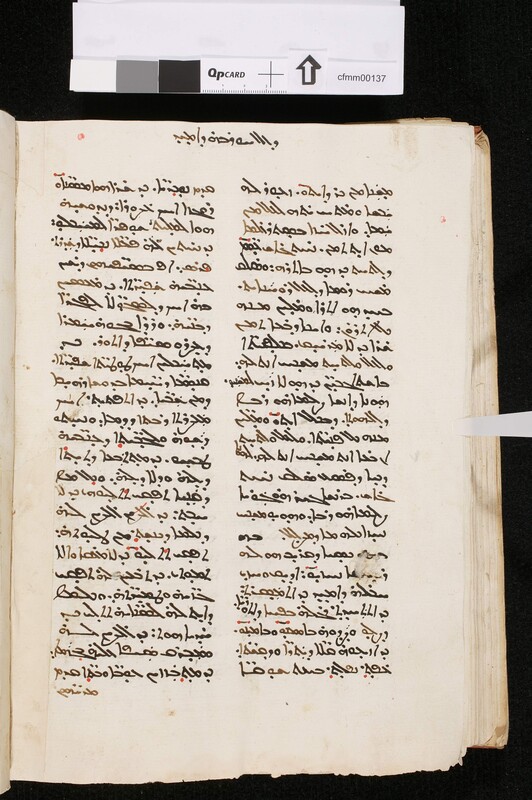

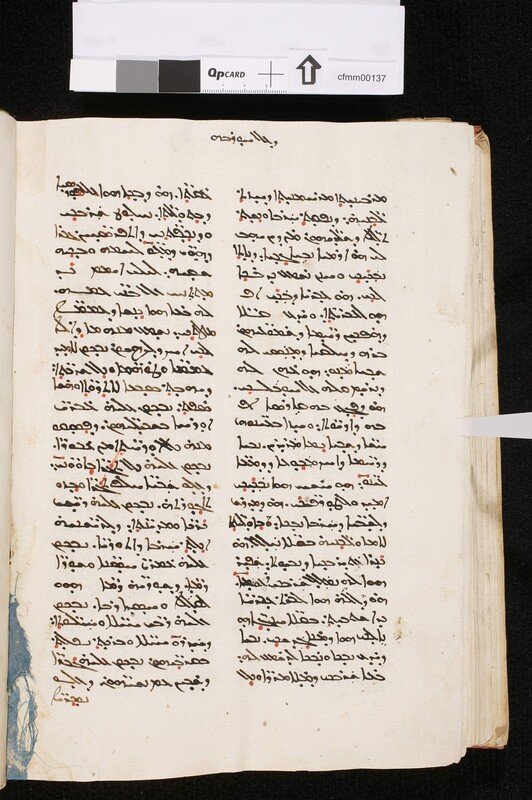

Catalogue Of The Mingana Collection of manuscripts

Margoliouth and Woledge outline Alphonse Mingana’s background and use that to clarify the period’s terminology. Mingana, born near Mosul in 1881, came from the Chaldean community—defined in the preface as the branch of the Nestorians that accepted the authority of Rome. His native language was Arabic; the ecclesiastical language of his community was Syriac, and the vernacular was a modern descendant of Syriac (Neo-Aramaic). Educated at the Lycée St. Jean in Lyon, he returned to Mosul to study at the Syro-Chaldean Seminary, run by French Dominicans for the two Syriac-speaking Uniate churches (Chaldean and “Syrian”). From 1902 to 1910 he taught Syriac, directed the Dominican press, traveled on the seminary’s behalf, and built two pillars of his later scholarly career: collecting Syriac manuscripts (about 70, including 20 on vellum, later burned during the First World War) and editing/publishing Syriac texts (including Narsai’s works, which earned him a papal doctorate).

Crucially for naming, the preface draws a clear contrast between Chaldeans and those whom it says have “in recent times” been called Assyrians—that is, the non-Catholic heirs of the Church of the East. In other words, Margoliouth and Woledge treat “Chaldean” as the Catholic, Rome-united stream of the historic East-Syrian tradition, and “Assyrian” as a modern label applied to the others. The passage thus frames Mingana’s identity and scholarly world within a Syriac Christian milieu where Assyrian as an ethnonym is presented as a recent usage, while Chaldean denotes the Uniate branch.

The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913

Wilmshurst opens by noting that the 1920s–1930s saw the rise of a common Assyrian identity, a struggle for an Assyrian homeland, and a turn away from Western missions—developments that mark a fundamentally new phase compared with the prewar history of the Church of the East. He then explains his terminology policy. For most of the period he studies (1318–1913), the church was commonly called “Nestorian” and its faithful were “Nestorians” (or “Chaldeans” for those who entered communion with Rome after 1552). In the sources of the time, “Nestorian” could be a term of abuse used by opponents of East Syrian theology, a badge of pride among its own defenders, and a neutral descriptor in other contexts. He gives concrete examples of East Syrian leaders who used the term positively: ‘Abdisho‘ of Nisibis (1318), Patriarch Eliya X of Mosul (1672), and Patriarch Shem‘un XVII Abraham (1842). Because the word has acquired a stigma in modern discussion, Wilmshurst avoids it as a label in his own prose and instead uses the theologically neutral “East Syrian.” To distinguish the post-1552 non-Catholic branch he uses “traditionalist.”

Wilmshurst also clarifies two other labels that appear in modern writing. First, the modern ethnonym “Assyrian”—often used today in roughly the same sense as “East Syrian” for the non-Catholic branch—was not in use for most of the period he covers, so he avoids it for historical accuracy. Second, “Chaldean,” which the Vatican first applied in the 15th century to identify Catholic converts from the Church of the East in Cyprus, and which was occasionally used by the Catholic patriarchs of Amid in the 18th century, only entered common currency after 1828 with the union of the Mosul and Amid patriarchates; for earlier centuries he therefore prefers “Catholic.” He adds a short note on transliteration: where Syriac and Arabic forms differ, he gives the Syriac form (reflecting his Syriac sources, especially manuscript colophons) and standardizes spellings accordingly—e.g., Denha, not Dinkha.

The Oxford dictionary of the Christian Church

The Oxford outlines the historical arc of the Church of the East. It notes a phase of repression under the Abbasid caliph al-Mutawakkil (847–861). Earlier witnesses such as Thomas of Marga’s ninth-century Book of Governors and references to Ishaq (d. 877) attest to the church’s intellectual life, while later the Mongols initially favored it. A major collapse followed in the fourteenth century after the Mongol dynasty’s conversion to Islam in 1295. Survivors who escaped Timur’s campaigns fled into the mountains of Kurdistan; their descendants, says the entry, have lived into modern times under the name “Assyrian Christians.” The article adds that the Church of the East’s liturgical language is Syriac and that its eucharistic anaphoras include those attributed to Theodore of Mopsuestia, Nestorius, and to Addai and Mari, the last retaining notably early features.

The entry is also a guide to sources and terminology. It remarks that the Church of the East has always called itself by that name, and it provides an extensive bibliography on the Nestorian controversy and church history (editions of Nestorius’s writings and classic modern studies by, among others, Loofs, Bethune-Baker, Labourt, and Assemani). It directs readers to a cross-reference on “Assyrian Christians” and to related bibliographies, indicating how modern scholarship labels the surviving Kurdish-mountain communities that stem from the historic Church of the East.

The Assyrian Church of the East: History and Geography

According to Christine Chaillot, the communities in question are the Eastern Syriac churches: the Assyrian Church of the East (officially “Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East” since 1976), its parallel jurisdiction the Ancient Church of the East (since 1968, same tradition, Old/Julian calendar), and their Catholic counterpart, the Chaldean Catholic Church (historically linked to the Church of the East). She also shows how names vary by place, especially in India (Chaldean Syrian Church of the East / Assyrian Church of the East; Syro-Malabar; Malankara branches)—which is why the same people can appear under different labels. In her wording, “Assyrian” is the name applied to followers of the Church of the East from the nineteenth century and, after World War I, it also carries a political-ethnic sense.

Chaillot highlights the role of missionaries in that modern consolidation: American and British workers operated among the faithful of the patriarchate of Kochanes (Urmia, Hakkari); the Archbishop of Canterbury founded an Anglican mission in 1881, reorganized in 1886 (Riley, Maclean, Browne). Their stated aim was to assist while preserving beliefs and ancestral customs, notably through schools and by translating and publishing the Church of the East’s books. Taken together, her pages indicate that the use and public prominence of “Assyrian” as a church-linked and later political-ethnic identity are modern (19th–20th century) developments. She does not claim that there was no earlier sense of peoplehood; rather, she shows that the label “Assyrian” and its broader, revived scope are recent and were amplified by missionary activity and twentieth-century usage.

The Nestorian Churches: A Concise History of Nestorian Christianity in Asia From the Persian Schism to the Modern Assyrians

Vine traces the Anglican engagement with the Nestorian Church from the late 19th century: after an appeal in 1868, Archbishop Tait sent E. L. Cutts to investigate (arriving 1876), which led to the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Mission to Assyrian Christians beginning in 1881. Early staff included Rudolph Wahl (to 1885), followed in 1886 by Canon A. J. Maclean, Athelstan Riley, and W. H. Browne; later, Canon W. A. Wigram worked there from 1902 to 1912. Headquarters were first at Urmia and moved in 1903 to Van. Vine remarks that the name chosen by the Church of England for its mission “has tended to come into general use,” so that Nestorian Christians were now usually called “Assyrians.” She adds that the Nestorians themselves styled their community “Christians” or “Syrians.” Vine situates the Anglican choice alongside other missionary efforts, Danish and Norwegian Lutherans, Baptists, and the Russian Orthodox. The Russian approach briefly drew Nestorian leaders toward union (notably an 1898 delegation to St. Petersburg); by 1900 Russia had built an Orthodox church at Urmia and opened schools, but its influence soon waned. In contrast, Rome’s solution was to make the Church Uniate (retaining rites while conforming to canon law), while Protestants sought to preserve the church as a distinct body, “the continuation of the Church of the Persian Empire”—yet to reform it from within, correcting doctrine and administration. That stance, Vine notes, sometimes created confused allegiances for Nestorians who benefited from Protestant schooling but hesitated to leave their historic church (she cites the case of Nestorius George Malech).

Later in the chapter, Vine carries the naming point forward into the First World War and its aftermath: in British discussions about Mesopotamia and Nestorian resettlement, she observes that the community was “now generally called Assyrians.” A footnote explains why the label had traction in English public culture, by the 1920s and 1930s, references in The Times, Hansard, Keesing’s Contemporary Archives, Headway, and Great Britain and the East were filed under “Assyrian” rather than “Nestorian,” and the patriarch raised no objection to either name. Vine’s narrative thus shows both the missionary origin of the term’s spread (via the Church of England) and the administrative-media routinization that made “Assyrian” the default Anglophone heading, even as local self-designations remained “Christians” or “Syrians.”

Saved from the Hands of the Assyrians

"Often they used to cross over and penetrate inside the borders, either because of the negligence of the agent in charge of the guard, or because of the tithe which was mercilessly imposed on them out of greed, and used to be captured and brought into Qamh by the Romans. When the man in question would see them, he treated them with a great deal of compassion, saying: “If you want, stay with us, or if you want, leave and go home in peace.” But if they left, he would send along provisions for them. Truly, my brothers, God has rewarded this man in that he saved him, together with all the people who were with him inside the fortress, from the hands of the Assyrians […] they heard: ‘He will not invade this town, but I will put a ring in the nose of this Assyrian and I will cause him to return with shame by the way in which he came.’ The Persians were fighting with all means, yet their tricks failed. They built mobile wooden houses to fill the ravine beside the city wall, but the Romans destroyed them. One night, thinking the defenders were asleep, countless Persians tried to climb the walls, shouting “Allahu Akbar,” but the Romans struck them down, piling their corpses in heaps. Thus all their efforts proved futile, for the helper of the Romans was the Lord."

In 769–770 CE, a massive multi-ethnic Abbasid army under ‘Abbas (brother of the Caliph) besieged the Byzantine fortress of Qamh. The chronicler describes the army’s diverse pagan and Muslim elements, their sins, and the heavy burden Arab rule placed on the local Syrian (Aramean) villagers. The Roman commander, Sergius, treated captured villagers with compassion. During the siege, the enemy taunted the defenders with boasts about past victories over many kings and lands. Despite being heavily outnumbered, Sergius and his men relied on prayer and faith, eventually repelling the attackers.

“Assyrian” is a figurative label for the Arab Muslim besiegers.

About the Destruction of Omid (Diyarbakir)

"The deceitful workers sent by Persia descended upon her, and with their swords they trampled her beautiful grapes, pressing her like clusters—the bodies of her children—and wine flowed within her, which the swords of Assyria pressed. Beautiful forms, beloved persons, were destroyed in the hasty trampling by captors when it was opened like a great winepress of blood."

About the Destruction of Omid (Diyarbakir)

"Nations and tribes and all families shall weep for OMID, which once gave abundance to the regions and now has perished. Travelers shall weep for her on their paths, for all roads have been cut off from passers-by. All merchants shall weep for her in their caravans, for captives entered instead of merchants and plundered her merchandise. The chiefs of cities and towns shall weep for her, for the sword of the Assyrians has devoured her leaders."

About the Destruction of Omid (Diyarbakir)

"Look and see the destruction of OMID when it was handed over, when its foot was caught in the trap of the Assyrians who hunted it with skill and persistence, when they stirred it with the sounds of bowstrings and bows."